1887.11.28 English

- Viktor Rydberg, 1828-1895 painted by the Swedish-Finnish painter, Albert Edelfelt, 1854-1905

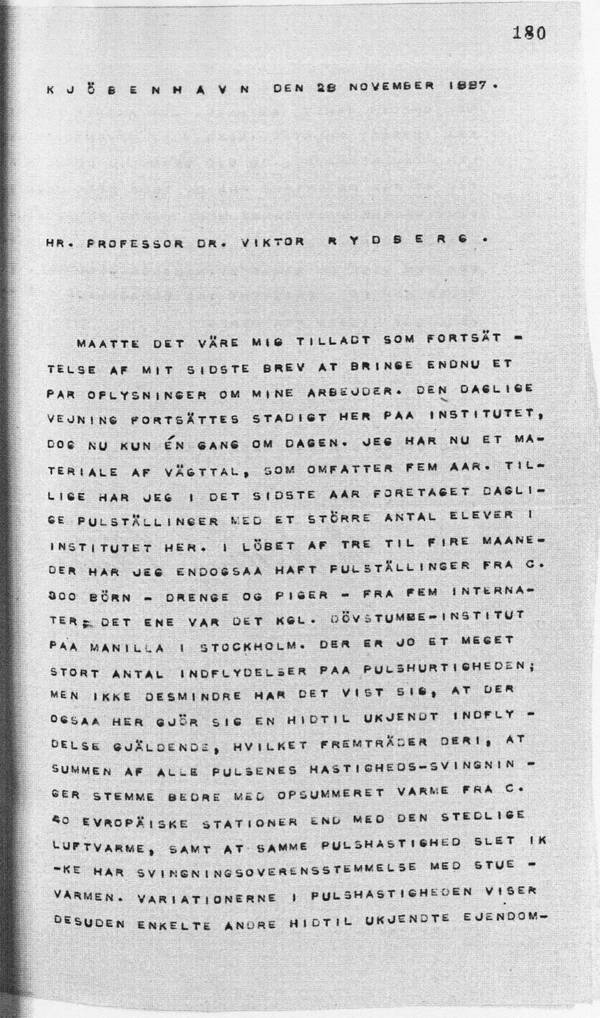

C O P E N H A G E N NOVEMBER 28, 1887DEAR PROFESSOR RYDBERG[1]

IN CONTINUATION OF MY LAST LETTER PLEASE ALLOW ME TO PRESENT SOME FURTHER INFORMATION ABOUT MY WORK. THE DAILY WEIGHING IS STILL ONGOING HERE AT THE INSTITUTE, HOWEVER BY NOW ONLY ONCE A DAY. I POSSESS BY NOW A MATERIAL OF WEIGHT DATA SPANNING FIVE YEARS. IN ADDITION, SINCE A YEAR BACK I HAVE CARRIED OUT DAILY PULSE COUNTINGS WITH A LARGE NUMBER OF PUPILS FROM THE INSTITUTE. DURING A PERIOD OF THREE TO FOUR MONTHS I HAVE EVEN HAD PULSE COUNTINGS[2] DONE FROM AROUND 300 PUPILS – BOYS AND GIRLS – FROM FIVE BOARDING SCHOOLS; ONE OF THESE WAS THE ROYAL INSTITUTE FOR THE DEAF-MUTE AT MANILLA[3] IN STOCKHOLM.

OF COURSE, MANY DIFFERENT FACTORS INFLUENCE THE PULSATION SPEED; NEVERTHELESS, IT HAS EMERGED THAT ALSO IN THIS RESPECT A HITHERTO UNKNOWN FACTOR MANIFESTS ITSELF, SHOWN BY THE FACT THAT THE SUM OF THE SPEED OSCILLATIONS FROM ALL THE PULSES COINCIDES MORE CLOSELY WITH THE ACCUMULATED HEAT FROM CA.40 EUROPEAN STATIONS THAN WITH THE LOCAL TEMPERATURE[4]. IN ADDITION TO THAT, THE PULSATION SPEED HAS NO OSCILLATION-CONGRUITY AT ALL WITH THE ROOM TEMPERATURE.

IN ADDITION, THE VARIATIONS IN THE PULSATION SPEED SHOWS A FEW OTHER HITHERTO UNKNOWN PECULIARITIES ON A YEARLY BASIS. I HOPE TO HAVE INTRODUCED PULSE COUNTINGS IN THE PUBLIC SCHOOLS IN COPENHAGEN AND EXPECT TO ACHIEVE A LEVEL OF CA. 2000 CHILDREN DAILY.

THE WEIGHINGS PRODUCE FAR MORE SECURE AND DETAILED OSCILLATIONS. THE WEIGHINGS OF THE LAST TWO YEARS HERE SHOW THE SAME PECULIARITIES IN TERMS OF OSCILLATIONS AS DO THE IN FRAGMENT THREE[5] ANALYSED THREE YEARS.

VERY BEST WISHES AND REGARDS FROM

YOURS RESPECTFULLY AND DEEPLY DEVOTED SERVANT

R. Malling-Hansen

[1] CB: This is the third letter from RMH to prof. Rydberg. The other two are 18871018UK and 18871126UK. A detailed ‘profile’ of prof. Viktor Rydberg can be found in connection with 18871018UK.

[2] CB: To my knowledge, this is the first time we learn that RMH also measured the pulse of the pupils. So far, I have not found any reference to this aspect in his ‘Fragments’ about Periods in the Growth of Children and Solar Heat from 1886.

[3] JMC: The Manilla institute was the first school in Sweden for deaf-mute (and blind) pupils, established already in 1809 and to this day very much active. It is very likely that RMH had a close relationship with this sister school and its principal Ossian Borg. Our website has a section with information about the Manila school, including pictures.

[4] CB: We know that RMH received statistics about temperatures from all over the world – and from no less than 40 European ’stations’. As far as I know he got them from the Danish Meteorological Institute, established in 1872.

[5] CB: Even if RMH very modestly is referring to Fragment 3, it is in fact his principal piece of work! The book and the collection of statistical tables and graphs, entitled ‘Periods in the Growth of Children and Solar Heat’ from 1886 and published in German and Danish.

Facts about the Manilla School, Stockholm, Sweden

- The Manilla School, the Public Instution for the Blind and Deaf-Mutes in Stockholm that cooperated with Malling-Hansen in his scientific studies. Photo: Jørgen Malling Christensen

The Manilla School, previously known as “The Public Institute for the Blind and Deaf-Mute”, was the first school established in Sweden for the teaching of deaf-mute and blind children and youngsters. The school started in 1809 and at the beginning admitted deaf, blind as well as pupils with learning difficulties (retarded). The founder was Pär Aron Borg – a devoted and dynamic teacher who was very highly regarded by the pupils. At the beginning of the 19th century he had started by teaching a few pupils on a private basis and in his own apartment. The very first pupil was the blind girl Charlotte Seyerling (who was later on to become a famous harp-player). The high level of knowledge and competencies of Borg’s pupils – confirmed through public examinations – was instrumental for the school to be rewarded with a yearly governmental support as from 1809, under patronage by Queen Hedvig Elisabeth Charlotta. By that move, Sweden had its very first school for blind and deaf pupils!

During an initial short period the school was situated on Drottningsgatan in the centre of Stockholm. In 1812 the school moved to “Djurgården” (a park area not far from the town centre), where it still remains. Initially both teachers and pupils were accommodated in a building that was already there when the school moved in. It was called “Upper Manilla” after a Spanish diplomat who was the previous owner of the area and had given the area this peculiar name in honour of his country that had colonized the Philippines and established its capital Manila. Through joints efforts by pupils and staff members the existing houses were reconditioned so as to make them more suitable for teaching purposes as well as for teachers’ and students’ accommodation. From the start Manilla was a boarding school. At the same time stables and a forge were put up.

During the epoch of Pär Aron Borg teaching was on the basis of the hand alphabet and sign language. As Sweden did not have at the time an established teaching method for this category of students, Pär Aron Borg himself devised the Swedish hand alphabet/sign language. Borg’s hand alphabet is being used to this day. In the beginning religious instruction and various types of craft education were given priority, as these were seen as essential at the time.

The manual craft skills were intended to help the pupils make a living once they left the school. For instance, boys were trained in crafts such as tailoring, shoe-repair, glazing, copper work, carpentry, joinery, bricklaying and horticulture. The girls could learn basketry, knitting, sewing and dressmaking, weaving, bakery or cooking – in accordance with their aptitude and interests.

Among the academic subjects were languages, reading, mathematics, and at a later stage geography, astronomy and science were added. Classes were given practically all year round, Monday to Saturday. As from 1827 four days of vacation were granted around the time of midsummer, and in the 1870s an extended summer holiday was introduced.

The institute had paying as well as pupils with a free place. The latter category included pupils enrolled at the expense of the Royal Household, as well as pupils paid for by the school’s own funds, or they could be pupils handpicked by their parish council. During the initial period of the school the enrolment age was between 6 and 36 years. In 1816 it was decided that the enrolment age should be 8-14 years, but in spite of this change older pupils continued to be accepted for a long period.

Initially the school did not have a strictly defined education or training period. The pupils would stay between 1 and 10 years – in exceptional cases even longer – depending on their individual abilities and development. However, normally they would stay for 7-8 years.

Enrolment occurred all year round, but mostly during the summer period or in autumn, when travels to the school were easier. Since many of the pupils had their family homes far away, many of them stayed at the school even during the holiday period. Consequently, some of them would spend practically their entire childhood and adolescence at the school.

The fact that the children were boarders also implied that they had to be looked after permanently. Hence, the teachers had to serve not only during teaching hours but also evenings, weekends and in holiday periods. Not until the end of the 19th century, when improved communications and logistics made it possible for the pupils to go back home during holiday periods, did the teachers’ workload become lighter.

The founder of Manilla, Pär Aron Borg, continued as principal until his death in 1839 and was then succeeded by his son Ossian Borg. Unlike his father, Ossian was of the opinion that academic subjects rather than artisan skills should be taught. Technical skills and crafts did continue as subjects for quite some time however, but teaching of practical skills was given lower priority than intellectual education.

During Ossian Borg’s period as principal the Manilla School changed from sign language to “oralism”, i.e. speech and lip-reading as the medium of instruction. This took place in the 1860s. In 1874 the school established a 2-year teacher training course for teachers of the deaf-mute, and this education continued until 1967 when it was moved to the Teacher Training College of Stockholm.

In 1864 the main building was inaugurated and it continues in use. The architect was J.A.Havermann. For more than 100 years this central school building continued to house the boarding facilities. In 1912 another floor was added to the building. The beautiful gymnasium for physical education was erected in 1870 and is still in use.

Teaching based on speech and lip-reading dominated the school until mid 1970s. For many years it was considered important that the pupils learned to become as “hearing” as possible. However, through research showing that sign language is a language in its own right – completely separated from Swedish – with its own grammar, syntax and structure, and by means of influence from parents associations as well as associations of the deaf-mute, gradually the methodology and philosophy of the education changed.

Jørgen Malling Christensen

For further information: se the website of the Manilla School: www.ma.spm.se